A sustainable wardrobe – Part 2, Raw materials: Manufactured fibres

Welcome to Raw Materials 101. This will be the first of two posts on this subject, so strap yourselves in people, we have a lot to cover. If you remember back to Part 1, I'd just done an audit on my wardrobe and was looking at the sheer quantity of stuff I own. Today we're going to look at what it's made from and whether I could be making better choices... I'm sure you can guess the answer there!

Before we get to the inside of my cupboard, I want to talk about the categories of fibres. At the top level there are two – natural fibres and manufactured, or man-made, fibres. Natural fibres are then split into another two groups – protein, or animal fibres, such as wool, alpaca, silk, angora, cashmere, etc, and cellulose, or plant fibres, such as cotton, linen and hemp.

The man-made fibres can also be divided in two. First are the regenerated fibres – these were a natural material at some point. Examples include viscose, lyocell and acetate. And last, there are the synthetic fibres – these are pure chemical constructions derived from sources such as petroleum, coal and gas. Some examples are polyester, nylon, acrylic and lycra. Yep, that acrylic that you're knitting with is made from natural gas and petroleum! Before starting this, I knew that polyester and acrylic were man-made, but I guess I'd never thought about what that really meant...

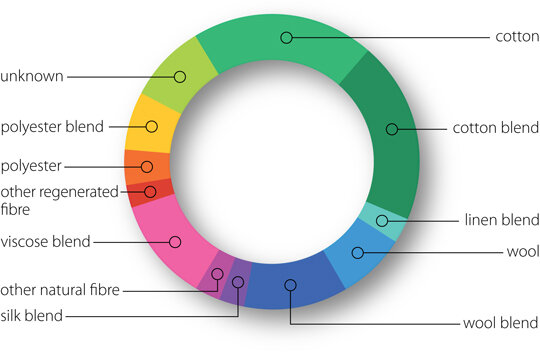

Now, back to the fibre content of my wardrobe. I did this chart in a pie shape so you get a better idea of percentages.

From here on in, we'll ignore the 'unknowns'. They are clothes so old that I can't read the labels anymore. To break it down, my wardrobe is 74 percent natural fibres/blends, 15 percent regenerated fibres/blends, and 11 percent synthetic or synthetic blend.

A quick word about blends. If you look at a clothing label, it will very often list a blend of fibres. The fibre making up the largest percentage will be listed first, followed by the others in ever decreasing amounts. My pie chart would have been unintelligible if I'd listed every blend, so they are grouped by the predominant fibre. The wool blends in my wardrobe include some that are 70 percent wool/30 percent cashmere, where others are 50 percent wool/50 percent nylon.

While only 11 percent of my wardrobe is synthetic, or synthetic blend, I was interested to go back and check what these items were. Unfortunately there were a couple of recent purchases – the easy way to fix that will be to look at the label before I buy next time – but a number of my going out/event dresses are also polyester – in particular, jersey wrap dresses. It only took a couple of minutes of Googling to find that my preferred style of dress could easily be made from something else.

The big-ticket polyester item in my wardrobe is an all-weather outdoor jacket. This will probably last me a lifetime, but I could have made a much more sustainable purchase by buying from Patagonia. These guys are pretty impressive and are doing a lot to lessen their environmental footprint. One of the good ways to buy polyester is when it's made from recycled water bottles, which is just what Patagonia is doing. Not only that, they take back their clothing that has reached the end of its life to recycle it again. While polyester might be made from a non-renewable resource, it can be recycled endlessly.

Another way synthetic fibres sneak into my wardrobe is through linings (which I didn't take into account in my audit), and the small amount of elastane, polyester or nylon added to nearly every T-shirt, pair of underpants or socks. I can find T-shirts without added synthetics, but even the organic cotton underwear I can find online still contains a small percentage of elastane. Maybe this is one of those least-worst choices I have to make for now.

The last thing I'll talk about today is regenerated fibres... These can be made from a surprising number of materials – wood, corn, soybean, milk and even coffee! The issue for me with these fibres is the chemicals needed to create them. Viscose (rayon) – which, bar one item, is the predominant regenerated fibre in my wardrobe – is made from wood pulp (or other cellulose fibres) dissolved in chemicals (sodium hydroxide, then carbon disulfide) until it becomes a liquid form, this is then run through a spinneret (that looks a bit like a shower-head) into a sulfuric acid solution that starts a chemical reaction to form the fibre filaments. The waste by-products aren't that fabulous either.

While it doesn't make an appearance in my wardrobe, I wanted to mention bamboo, as you might not be aware that it's often made using the process just described. It can be made in a similar way to linen, a mechanical process, but it's cheaper and easier to make it as a regenerated fibre. The US and Canada have ruled that bamboo made by regeneration can no longer be labelled as bamboo – in the same way you don't label rayon as wood fibre – but in Australia "there is no national mandatory information standard presently in place for fibre content labelling" according to The Council of Textile & Fashion Industries of Australia website, and much of the bamboo product here is regenerated. So, be extra careful when buying bamboo. While arguably, bamboo is more sustainable than farming trees, the regeneration process is definitely not sustainable, and the properties that are so often spruiked in regards to bamboo eg anti-bacterial, are completely destroyed using that production process.

The most sustainable of the regenerated fibres is lyocell. You may know it better by its trade name Tencel. Remember those jeans you had in the 90s? Turns out they're reasonably sustainable. Lyocell is made from farmed trees with a non-toxic solvent that can be 99 percent recycled during the production process, making it an almost closed-loop system. There are some issues with the chemicals used in the next stage of production ie turning them into garments, but we'll look at that in Part 4 – Fibre to fabric.

I guess the thing with all these new fibres coming onto the market is to do a little research before you purchase. I know it takes time, but the internet makes the research process a whole lot easier and faster than it used to be. Just make sure you're taking your information from a credible source.

Next month I'll look at the biggest fibre change that's going to have to happen in my wardrobe to make it sustainable – the removal of conventional cotton. I'll also give you some resources for choosing more sustainable yarns and fabrics for your crafts, along with more clothing links.

In the meantime check out the Pinterest pages I'm building for this series – I'll be adding to them every month – A Sustainable Wardrobe, Sustainable Textile Supplies and Sustainable Fashion movement, which will provide links to stories, news articles and campaigns.

Waterproof jacket from Patagonia or Nau.

Underwear from Pact or Bhumi – Target in Australia also stock organic cotton underpants.

Organic cotton T-shirts (and other things) from Rawganique, and in Australia – Etiko and The Organic T-Shirt. There are a ton of other suppliers out there for organic cotton tees, but I've kept to the plain T-shirts, as I don't really do clothes with stuff written on it.

Replacement jersey wrap dresses could be found at:

Before we get to the inside of my cupboard, I want to talk about the categories of fibres. At the top level there are two – natural fibres and manufactured, or man-made, fibres. Natural fibres are then split into another two groups – protein, or animal fibres, such as wool, alpaca, silk, angora, cashmere, etc, and cellulose, or plant fibres, such as cotton, linen and hemp.

The man-made fibres can also be divided in two. First are the regenerated fibres – these were a natural material at some point. Examples include viscose, lyocell and acetate. And last, there are the synthetic fibres – these are pure chemical constructions derived from sources such as petroleum, coal and gas. Some examples are polyester, nylon, acrylic and lycra. Yep, that acrylic that you're knitting with is made from natural gas and petroleum! Before starting this, I knew that polyester and acrylic were man-made, but I guess I'd never thought about what that really meant...

Now, back to the fibre content of my wardrobe. I did this chart in a pie shape so you get a better idea of percentages.

From here on in, we'll ignore the 'unknowns'. They are clothes so old that I can't read the labels anymore. To break it down, my wardrobe is 74 percent natural fibres/blends, 15 percent regenerated fibres/blends, and 11 percent synthetic or synthetic blend.

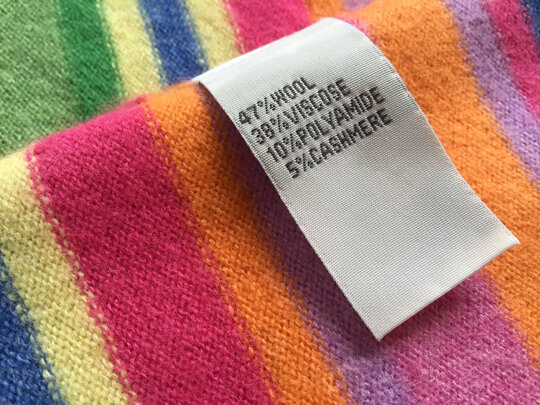

A quick word about blends. If you look at a clothing label, it will very often list a blend of fibres. The fibre making up the largest percentage will be listed first, followed by the others in ever decreasing amounts. My pie chart would have been unintelligible if I'd listed every blend, so they are grouped by the predominant fibre. The wool blends in my wardrobe include some that are 70 percent wool/30 percent cashmere, where others are 50 percent wool/50 percent nylon.

|

| Clothing from my wardrobe containing a blend of natural, regenerated and synthetic fibres. |

While it doesn't make an appearance in my wardrobe, I wanted to mention bamboo, as you might not be aware that it's often made using the process just described. It can be made in a similar way to linen, a mechanical process, but it's cheaper and easier to make it as a regenerated fibre. The US and Canada have ruled that bamboo made by regeneration can no longer be labelled as bamboo – in the same way you don't label rayon as wood fibre – but in Australia "there is no national mandatory information standard presently in place for fibre content labelling" according to The Council of Textile & Fashion Industries of Australia website, and much of the bamboo product here is regenerated. So, be extra careful when buying bamboo. While arguably, bamboo is more sustainable than farming trees, the regeneration process is definitely not sustainable, and the properties that are so often spruiked in regards to bamboo eg anti-bacterial, are completely destroyed using that production process.

The most sustainable of the regenerated fibres is lyocell. You may know it better by its trade name Tencel. Remember those jeans you had in the 90s? Turns out they're reasonably sustainable. Lyocell is made from farmed trees with a non-toxic solvent that can be 99 percent recycled during the production process, making it an almost closed-loop system. There are some issues with the chemicals used in the next stage of production ie turning them into garments, but we'll look at that in Part 4 – Fibre to fabric.

I guess the thing with all these new fibres coming onto the market is to do a little research before you purchase. I know it takes time, but the internet makes the research process a whole lot easier and faster than it used to be. Just make sure you're taking your information from a credible source.

Next month I'll look at the biggest fibre change that's going to have to happen in my wardrobe to make it sustainable – the removal of conventional cotton. I'll also give you some resources for choosing more sustainable yarns and fabrics for your crafts, along with more clothing links.

|

| Some rare acrylic in my stash – thankfully, as a whole, the stash is largely natural fibre. |

Today's resources

Waterproof jacket from Patagonia or Nau.Underwear from Pact or Bhumi – Target in Australia also stock organic cotton underpants.

Organic cotton T-shirts (and other things) from Rawganique, and in Australia – Etiko and The Organic T-Shirt. There are a ton of other suppliers out there for organic cotton tees, but I've kept to the plain T-shirts, as I don't really do clothes with stuff written on it.

Replacement jersey wrap dresses could be found at:

- Australian brand Audrey Blue, who are Fair Trade and Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS) certified.

- Australian brand Smitten Merino.

- Conscious Clothing, based in Michigan US and dedicated to using the most eco-friendly and sustainable fabrics, dyes, inks, and products available.

- Or I could buy organic cotton jersey from Alabama Chanin and make it myself!